Kalaupapa: Land of Exile and Refuge

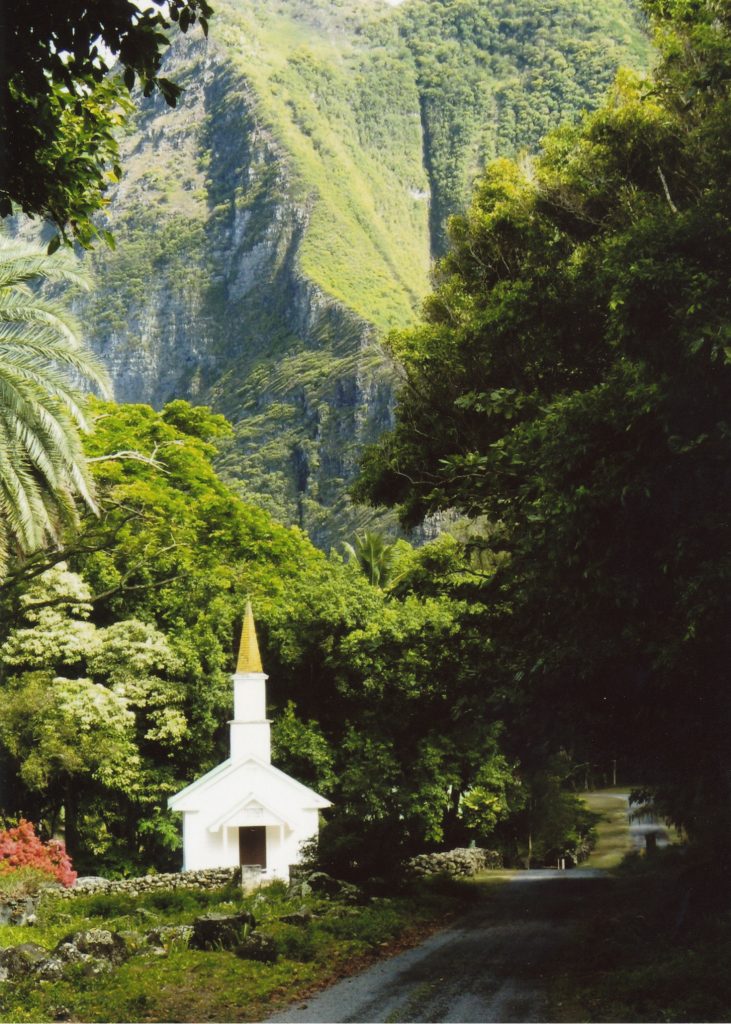

On the island’s north shore, soaring green cliffs and a windswept coast hem in the small village of Kalaupapa, accessible only by boat, private plane charters, or a 3.5 mile hike. The peninsula’s natural beauty seems to epitomize paradise, yet Kalaupapa’s idyllic appearance hides its residents’ surprisingly dark history.

In the early 1800s, foreign diseases spread through the Hawaiian islands as a result of increased contact with Europeans. By the late 1800s, leprosy was ravaging the native Hawaiian population, which lacked immunity to the illness. In desperation, King Kamehameha V designated the Kalaupapa Peninsula on Molokai as a leprosy colony in 1865. New legislation mandated that any man, woman, or child suspected of having the disease be arrested and sent to Kalaupapa. The patients were shipped to the colony to live in isolation, separated from their families and left to die. Kalaupapa’s early patients were not provided with adequate shelter, food, and medical care.

Beginning in 1873, living conditions at Kalaupapa began to improve thanks to the efforts of Father Damien and the support of King Lunalilo and later King Kalakaua. Some na kokua, or helpers, voluntarily accompanied their sick loved ones to the settlement, providing both the compassion and the extra workers that the colony lacked. Homes were constructed, schools and community activities were organized, and medical care was provided.

At the close of the 19th century, Kalaupapa’s population peaked at approximately 1100 people. Yet while the infrastructure and resources at Kalaupapa improved over the years, the barriers between patients and non-patients remained. Fences and railings separated workers from patients and contact between the two groups was extremely limited.

They’re really kind people, and it’s kind of an amazing thing considering what they’ve been through. I remember this one man telling us about how when they came to Honolulu for treatment, people would treat them like they weren’t there.

During the 1940s and 1950s, researchers developed the first effective leprosy treatments, and after using these new drug regimens, patients were no longer contagious. Finally in 1969, Hawaii’s mandatory quarantine laws were abolished.

Medical advances and scientific research proved leprosy was neither incurable nor highly contagious as was previously believed. In order to shake off its persisting stigma, leprosy was officially renamed as Hansen’s disease after the scientist who discovered M. leprae, the bacteria that causes the infection.

Despite the end of the quarantine laws, many patients chose to remain at Kalaupapa for the rest of their lives, taking refuge and finding peace in what had once been their land of forced exile. The settlement was established as a national park in 1980 and is now home to just a handful of patients, their caregivers, and National Park Service and Department of Health workers. In a 2015 report, Hawaii News Now states that only sixteen patients remained alive and only six were full-time residents. According to the National Parks Service, access to the park is restricted to just 100 visitors per day to protect the privacy of the remaining patients and to preserve Kalaupapa’s land, sacred because of its history and its value to Hawaii’s ecological diversity. Tourists have to obtain permits ahead of time to visit the park and no one under 16 is allowed.

HBA’s curriculum director Pat Ota made her first trip to Kalaupapa in the early 90s as part of a missions team from Olivet Baptist Church. In describing Kalaupapa, Ota said, “It is like what you would imagine old Hawaii was like, because it’s so isolated and a really small rural community. There aren’t many people in this isolated community and there are no children. Pets provide some companionship and are well cared for.”

When Ota travels to the settlement, she stays at a local church and assists the residents with any tasks they may find difficult. “It can be yard work, or a lot of times we’ll clean the brass in the church. Back in my earlier trips when there were more people, some people would do haircuts…different people do different things,” she said.

Beyond serving the community with practical tasks, Ota and other volunteers enjoy connecting with the residents on a personal level. “We always bring cookies and share meals with them, ” she said.

Since her first visit in the 90s, Ota has made several trips back to Kalaupapa to volunteer. Her most recent trip was in October 2016. She has bonded with several of the patients, but notes that the community has changed significantly over the years. “A lot of the people I knew from before have passed away,” she said. However, Ota continues to be amazed at the love she’s received from the patients themselves. “They’re really kind people, and it’s kind of an amazing thing considering what they’ve been through. I remember this one man telling us about how when they came to Honolulu for treatment, people would treat them like they weren’t there,” she said.

A few years ago, Bible teacher Tony Traughber also had a chance to visit Kalaupapa with a missions team from Olivet Baptist Church. During his extended weekend trip, Traughber visited various locations around the settlement and assisted with cleaning, yard work, and a church service. Unlike Ota, Traughber did not have the opportunity to talk to the patients there. However, he noted that the settlement seemed to be at a turning point. “It was odd because they aren’t getting new patients. Once that last patient has passed, [Kalaupapa] is going to become a reminder of what it used to be,” he said.

As Kalaupapa’s patient population dwindles, the settlement’s future is uncertain. The National Parks Service has proposed four different courses of action, termed “alternatives”. Their “preferred alternative” would allow children to visit Kalaupapa with adult supervision and remove the 100 person per day visitor cap. The emphasis of this plan is on the “stewardship of Kalaupapa’s lands in collaboration with the park’s many partners.”

Support for this proposal has been mixed, according to the Hawaii News Now report referenced earlier. Supporters believe it will raise awareness of Kalaupapa’s past and enable visitors to learn through firsthand experience. Opponents of the proposal argue that removing visitation restrictions will destroy the sacredness of the land, damage the pristine natural environment, and diminish the weight of the patients’ struggle.

Regardless of what Kalaupapa’s next chapter holds, the impact of its past and its people is undeniable. Despite not being able to spend much time with the patients themselves, Traughber was inspired by their stories and their quiet strength. “I was struck by how sad [Kalaupapa’s story of origin] was, but also the courage it would take to survive and to not give up and to persevere,” he remarked. “It is an admirable thing for anyone that was able to live there, survive, and in their own way, thrive.”

1 Comment

Absolutely love this article! I would definitely love to see the eagle eye feature more articles about hawaiian culture and history. sovereignty is definitely a controversial topic but i think the eagle eye would be able to objectively approach it. keep up the good work!